The Kodak Retina IIIc Saga Continues…

The Kodak Retina IIIc is not a perfect camera by any means, but its strengths far outweigh its few flaws. Its remarkably compact size, exceptional lens quality, and innovative features combine to make it a standout choice for photographers who truly appreciate the unique charm and subtle challenges of vintage gear. Sure, the infamous cocking rack can be a persistent headache, and tracking down a reliable, well-functioning example can sometimes be a gamble. But when you get it just right—whether through careful, patient selection or, in my case, a little bit of creative parts-swapping—the Retina IIIc becomes a camera that genuinely rewards you with every single shot, making the whole journey well worth it.

The anticipation of receiving a new to me camera in the mail is a feeling that resonates deeply with any photography enthusiast. After the trials and tribulations recounted in my previous article about purchasing a Kodak Retina IIIc on eBay, I was cautiously optimistic when another Retina IIIc arrived in the mail. My last order took a grueling three weeks to arrive, so when this one showed up in just five days, I was nothing short of astonished. The speed of delivery felt like a small victory, a promising start to what I hoped would be a better experience with this iconic folding camera.

There’s something undeniably thrilling about unboxing a vintage camera, especially one as storied as the Kodak Retina IIIc. It’s not just a piece of equipment; it’s a tactile connection to photographic history, a vessel of potential adventures wrapped in a sleek, compact body. As I carefully unwrapped the camera from its packaging and slid it out of its well-worn leather case, I couldn’t help but feel a rush of excitement. Life, I’ve come to realize, is not like a box of chocolates, as Forrest Gump famously quipped. It’s more like an eBay order, you truly never know what you’re going to get. Sometimes, that unpredictability leads to a nightmare; other times, it delivers something even better than you’d hoped.

As I held the Retina IIIc in my hands, I noticed something immediately; the previous owner had etched their personal information into the top plate. It was a minor imperfection, a testament to the camera’s trajectory through time and human hands before reaching my possession. My primary concern, however, wasn’t the cosmetic imperfections but the condition of the cocking rack—a notorious weak point in the Retina series, including the IIa, IIc, IIIc, IIIC, and IB models. My previous Retina IIIc had arrived with a faulty cocking rack, rendering it nearly unusable, and I was determined not to repeat that disappointment. If this one’s cocking rack was also defective, I was ready to swear off Kodak Retinas for good.

To my relief, the cocking rack was in mint condition. I spent some time meticulously inspecting the camera, testing its mechanical functions, and familiarizing myself with its quirks. The shutter fired smoothly, the aperture ring clicked with satisfying precision, and the film advance lever, uniquely located on the bottom of the camera, operated as it should. But, as with any vintage purchase, there were imperfections. I noticed a small spot on the front lens element, and the built-in light meter was sluggish, struggling to respond accurately to changes in light. These issues, while not deal breakers, meant the camera wasn’t quite ready for action.

In my previous article, I had mentioned the possibility of using my first Retina IIIc as a parts body if its issues proved insurmountable. That’s exactly what I ended up doing. The first camera, despite its faulty cocking rack, had a pristine front lens element, a fully functional light meter, and an unmarred top plate. With a bit of careful disassembly and some tinkering, I swapped these components onto the new camera. The result? One fully functional, almost perfect Kodak Retina IIIc, albeit with mismatched serial numbers.

For some, mismatched serial numbers might be a dealbreaker, a blemish on the camera’s collectible value. But I’m not a collector, I’m a photographer that uses my cameras. My goal isn’t to display this Retina IIIc on a shelf; it’s to take it out into the world, capture moments, and tell stories through its lens. With the best parts from both cameras combined, I now had a folding camera that was not only functional but also a joy to use.

Last week, I took my newly restored Retina IIIc to green valley park here in Payson, AZ to test its capabilities. As I framed shots and adjusted settings, an older gentleman walking his dog approached me. He watched me for a moment before asking, with genuine curiosity, “How are you able to take pictures if you’re blind?”

It was a question I’ve heard before, and in that moment, a dozen responses flashed through my mind, some witty, some defensive. Instead, I opted for a simple analogy: “If you’d been doing something for 40 years, would you stop just because you couldn’t see anymore?” He paused, nodded thoughtfully, and said, “That’s a great point.” With a smile, he continued on his walk, his dog trotting happily beside him.

That interaction stuck with me. Photography, for me, is more than just seeing through a viewfinder. It’s about muscle memory, intuition, and a deep understanding of the craft honed over decades. The Retina IIIc, with its unique design and tactile controls, complements this approach perfectly.

The Kodak Retina IIIc is a remarkable piece of engineering, a camera that was undeniably ahead of its time when it was introduced in the 1950s. Its compact, folding design made it portable, while its high-quality Schneider-Kreuznach lens delivered sharp, vibrant images. The built-in light meter, a rarity for its era, added a layer of convenience that set it apart from many of its contemporaries. But, like any piece of vintage technology, it has its flaws—chief among them, the infamous cocking rack.

The cocking rack is the Achilles’ heel of the Retina series. Models like the IIa, IIc, IIIc, IIIC, and IB are all susceptible to issues with this critical component, which advances the film and cocks the shutter. A faulty cocking rack can render an otherwise excellent camera useless, as I learned the hard way with my first Retina IIIc. For anyone considering purchasing one of these models, my advice is simple. Seek out a camera that has been recently serviced (CLA’d—cleaned, lubricated, and adjusted) or one with a well documented history. If you’re buying on a budget, as I do, be prepared to purchase two cameras to cobble together one fully functional unit. It’s a gamble, but when it pays off, the reward is a camera that’s a joy to shoot with.

One of the standout features of the Retina IIIc, compared to its sibling the IIc, is the inclusion of a light meter. This meter works in conjunction with the camera’s Exposure Value (EV) system, a method of setting exposure that some photographers love and others loathe. For me, it’s a game-changer, especially given my severe visual impairment.

The EV system locks the shutter speed and aperture together based on a single EV number, simplifying the exposure process. Once the EV is set, adjusting one parameter automatically adjusts the other to maintain the correct exposure. For someone like me, who relies heavily on tactile feedback and muscle memory, this system is a blessing. Setting the EV number is straightforward, and from there, it’s just a matter of counting the clicks to dial in the desired shutter speed. What initially seemed like a quirky, outdated system has become one of my favorite features of the Retina IIIc. Like the camera’s bottom-mounted advance lever, it’s a design choice that feels foreign at first but becomes second nature with practice.

The Kodak Retina IIIc is not a perfect camera, but its strengths far outweigh its flaws. Its compact size, exceptional lens, and innovative features make it a standout choice for photographers who appreciate the charm and challenge of vintage gear. Yes, the cocking rack is a persistent issue, and sourcing a reliable example can be a gamble. But when you get it right—whether through careful selection or, in my case, a bit of parts-swapping—the Retina IIIc is a camera that rewards you with every shot.

For me, photography is about more than just capturing images, it’s about the experience, the process, and the stories that unfold along the way. Whether it’s the thrill of unboxing a new-to-me camera, the satisfaction of resurrecting a broken one, or the unexpected conversations sparked by a day at the park, the Retina IIIc has already given me more than I could have hoped for. If you’re willing to embrace its quirks and invest a little patience, this classic camera might just surprise you, too.

What are your thoughts? Are you a Retina skeptic? Let me know what you think in the comments. Photographs are below the article.

Kodak Retina IIIc: A Tale of eBay and Vintage Cameras

The Kodak Retina IIIc is a beautiful piece of photographic history, a folding camera from the 1950s that promises sharp images and a nostalgic shooting experience. With its sleek design, Xenon f/2 lens, and uncoupled light meter, it’s a gem for collectors and film photography enthusiasts like me. However, my journey to acquire a working Retina IIIc has been nothing short of a rollercoaster, filled with anticipation, frustration, and a few hard-learned lessons about buying vintage cameras online that I should have already grasped. Let me take you through my saga, from the thrill of clicking “Bid Now” on eBay to the heartbreak of a broken cocking rack.

The Kodak Retina IIIc is a beautiful piece of photographic history, a folding camera from the 1950s that promises sharp images and a nostalgic shooting experience. With its sleek design, Xenon f/2 lens, and uncoupled light meter, it’s a gem for collectors and film photography enthusiasts like me. However, my journey to acquire a working Retina IIIc has been nothing short of a rollercoaster, filled with anticipation, frustration, and a few hard-learned lessons about buying vintage cameras online that I should have already grasped. Let me take you through my saga, from the thrill of clicking “Bid Now” on eBay to the heartbreak of a broken cocking rack.

It all began about a month ago when I spotted a Kodak Retina IIIc listed on eBay. The listing photos showed a camera in pristine condition, nestled in its original leather case, with a promise of functionality. I was sold. I placed my order and eagerly awaited its arrival, imagining the stunning photographs I’d soon capture with its legendary Xenon f/2 lens, known for its sharpness and beautifully shallow depth of field.

The seller, based in Washington state, opted for USPS’s cheapest ground shipping option. What followed was a logistical nightmare that could only be described as a comedy of errors. The package embarked on a bizarre cross-country journey, starting in Washington, making a pit stop in Portland, Oregon, then heading to Los Angeles, California, before finally landing in Phoenix, Arizona, an hour and a half drive from Payson. Nine days after the order, I was thrilled to see it had arrived in Phoenix. My excitement was short lived.

For reasons unknown, the camera sat in a hot desert distribution center for three days before being inexplicably shipped back to Washington state. I contacted USPS, hoping for clarity, but they were as baffled as I was. “We don’t know why it was sent back,” they told me, offering little comfort. Another week passed before the camera began its return journey to Phoenix. Two more days, and it finally landed in my mailbox three weeks after I’d placed the order. A week’s delay is understandable, but three weeks? That’s enough to test anyone’s patience.

When the package finally arrived, I tore into it with the enthusiasm of a kid on Christmas morning. The camera looked impeccable, still snug in its leather case, with no visible scratches or dents. It appeared to be the pristine specimen promised in the eBay listing. Eager to test it, I cocked the shutter and fired it. The satisfying click of the shutter was music to my ears. I tried it again and nothing. The advance lever refused to budge. My heart sank.

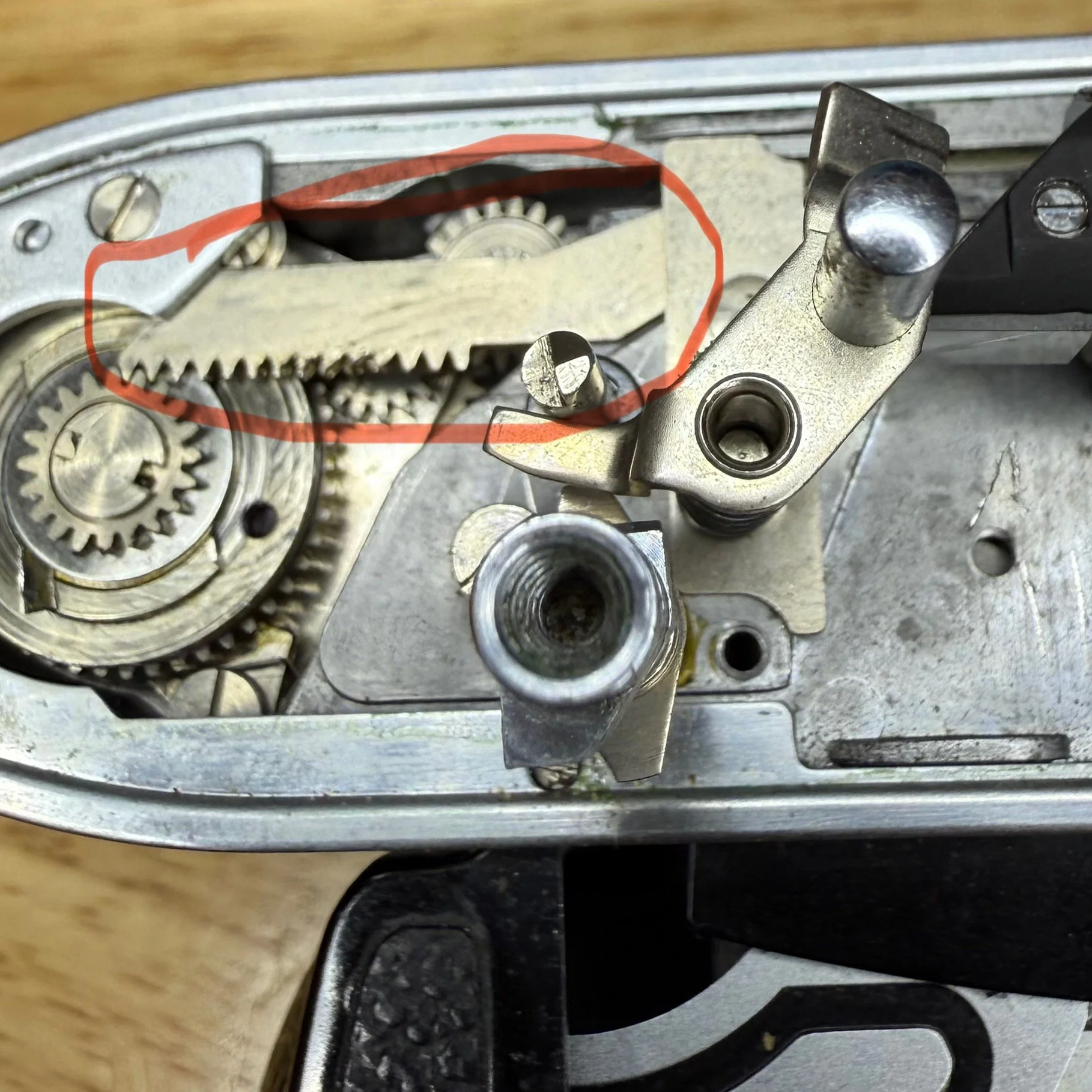

Determined to diagnose the issue, I carefully removed the top cover of the camera. What I found was devastating: the cocking rack, a critical component of the Retina IIIc’s film advance mechanism, was damaged beyond repair. For those unfamiliar, the cocking rack is a delicate part that engages the gears to advance the film and cock the shutter. It’s a testament to the brilliance of the Retina’s engineers, but also its Achilles’ heel.

The Kodak Retina line, produced between 1954 and 1957 for the IIIc model, is a marvel of mid-20th-century engineering. These cameras were ahead of their time, offering compact designs, high-quality lenses, and features like the uncoupled light meter on the IIIc, which I was particularly excited about as a tool for manual exposure calculations. However, the cocking rack is a notorious weak point. From my research and discussions with other collectors, I’ve learned that several factors can lead to its failure.

The most common issue is the guide screw that keeps the cocking rack aligned. Over time, this screw can loosen, allowing the rack to shift and misalign with the gears. This slight movement can wreak havoc on the delicate mechanism, causing irreparable damage. Another frequent culprit is old grease in the shutter mechanism. In colder months, this grease can harden, essentially turning to concrete. If someone forces the advance lever when the shutter is stuck, the rack can be pushed over the gears, bending or breaking it in the process.

There’s also the possibility of human error. The Retina IIIc is over 70 years old, and many have been serviced (or “CLA’d”—cleaned, lubricated, and adjusted) over the decades. An inexperienced technician could mishandle the delicate components, leading to issues like the one I encountered. As someone who’s also over 50, I can sympathize with the Retina IIIc—things start to creak and break down around this age, don’t they?

Despite this setback, my affection for the Kodak Retina IIIc remains unshaken. I already own a Retina IIc, which I adore for its compact size and stellar image quality, but the IIIc offers something extra: that uncoupled light meter. For someone like me, having a built-in meter is a godsend. Plus, the Xenon f/2 lens is a dream, delivering tack-sharp images with a creamy bokeh that’s perfect for portraits or low-light shooting.

The Retina IIIc is a folding camera, meaning the lens retracts into the body when not in use, making it surprisingly portable for its era. It’s a blend of form and function that feels like holding a piece of history in your hands. When it works, it’s a joy to shoot with, offering a tactile, deliberate experience that modern digital cameras can’t replicate.

Faced with a broken cocking rack, I weighed my options. A new old stock (NOS) cocking rack on eBay was listed for $40, but there’s no guarantee it would solve all my problems, and installation requires precision I wasn’t confident I could muster. Instead, I took a leap of faith and ordered another Retina IIIc from a different seller, this time for a bit less than the cost of the replacement part. It’s set to arrive in a few days, and I’m cautiously optimistic (fingers crossed) that it won’t suffer from the same issue.

This isn’t my first rodeo with vintage cameras gone wrong. A few years back, I went through a similar ordeal with a Mamiya Six, buying four of them over the course of a year in hopes of finding one that worked decently. Frustration eventually got the better of me, and I sold them all. I’m determined not to let history repeat itself with the Retina IIIc.

Despite the challenges, there’s something magical about shooting with a camera like the Kodak Retina IIIc. These machines were built in an era when craftsmanship was paramount, and every click of the shutter feels like a connection to the past. The Retina IIIc, with its blend of engineering ingenuity and optical excellence, embodies that spirit. Yes, my first attempt at owning one was a bust, but I’m not giving up. The promise of capturing stunning images with that Xenon f/2 lens keeps me hopeful.

As I wait for my second Retina IIIc to arrive, I’m reminded why I love film photography. It’s not just about the final image, it’s about the journey, the quirks, and the stories that come with these vintage treasures. Here’s hoping my next Retina IIIc will be a keeper. In the meantime, I’ll keep my fingers crossed and my eBay alerts on.

If you’ve got your own tale of vintage camera triumphs or disasters, I’d love to hear it. And if you’re eyeing a Retina IIIc, tread carefully but don’t let my misadventure scare you off. When it works, it’s a camera worth chasing.

Kodak Retina IIc

For decades, I dismissed Kodak cameras, associating them with the mass-produced, lowquality designs of the 1970s and 1980s. My career as a professional photographer and enthusiast led me to favor Minolta film cameras and later Sony and Canon digital systems. However, my recent exploration of 35mm folding cameras, driven by the need for a rangefinder-equipped model suitable for my visual impairment, brought me to reconsider Kodak’s Retina line. This article chronicles my journey from skepticism to admiration, culminating in the acquisition and use of a Kodak Retina IIc.

For decades, I dismissed Kodak cameras, associating them with the mass-produced, lowquality designs of the 1970s and 1980s. My career as a professional photographer and enthusiast led me to favor Minolta film cameras and later Sony and Canon digital systems. However, my recent exploration of 35mm folding cameras, driven by the need for a rangefinder-equipped model suitable for my visual impairment, brought me to reconsider Kodak’s Retina line. This article chronicles my journey from skepticism to admiration, culminating in the acquisition and use of a Kodak Retina IIc.

Growing up in the late 1970s and 1980s, I encountered Kodak cameras that epitomized the era’s "plastic fantastic" and Bakelite designs. These cameras, often flimsy and prone to failure, earned a poor reputation among photographers, frequently relegated to the status of gag gifts. While Kodak’s film remained the gold standard, their cameras, in my view, fell short of the quality offered by competitors like Minolta, which I relied on for years. This bias shaped my equipment choices, leading me to overlook Kodak’s offerings for much of my career.

As a legally blind photographer, I sought a compact 35mm folding camera with a rangefinder to simplify focusing, given my inability to judge distances accurately. Initially, I turned to Voigtländer’s Vito series, which I found reliable and well-designed. However, the only Vito model with a built-in rangefinder, the Vito III, was prohibitively expensive. This led me to revisit Kodak’s Retina line, specifically the IIc and IIIc models, which combine portability with rangefinder functionality.

My perspective shifted after discovering Retina Rescue, a website by Chris Sherlock, a renowned expert in vintage camera repair. Sherlock’s detailed insights into the Retina series, coupled with his engaging YouTube channel, provided a wealth of knowledge about the cameras’ engineering and history. His work challenged my assumptions about Kodak and inspired me to seek out a Retina IIc or IIIc.

After a thorough search, I found an eBay auction for a mint-condition Retina IIc, complete with 35mm and 80mm accessory lenses. Winning the auction at a price well below market value felt like a stroke of luck. When the camera arrived, it was pristine, with all components functioning as described. The Retina IIc’s Exposure Value (EV) system, which couples shutter speed and aperture based on a light meter reading, proved intuitive and accessible, particularly for someone with visual limitations.

On Father’s Day, I tested the Retina IIc during an outing to Show Low and Pinetop, Arizona, with a stop at the Mogollon Rim overlook in Payson. The camera’s bottom-mounted film advance lever required some adjustment, but the rangefinder made focusing effortless. Shooting at sunset, I captured images of the valley and winding road below, and the results were striking—sharp, contrasty, and well-exposed across various settings. The Retina’s optical quality and design exceeded my expectations.

The Retina IIc has reshaped my view of Kodak cameras, revealing a level of craftsmanship made in Germany I had not associated with the brand. Its compact design, rangefinder precision, and reliable performance make it an excellent choice for photographers, especially those with visual impairments. I highly recommend exploring Chris Sherlock’s Retina Rescue for anyone interested in vintage cameras. For collectors and enthusiasts, the Retina series offers a unique blend of history and functionality.

I’d love to hear from fellow photographers: Do you collect Kodak Retinas? What are your experiences with these cameras? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Zeiss Ikon Super Ikonta 531/2

It is rare these days to find a gem for the price of a rock on eBay. About a month ago, I put in a low bid for a Super Ikonta more for a laugh than anything else. The starting bid was $10 for this beautiful piece of German engineering. I threw out a small bid of $20 just to see what happened. About a week went by and I forgot about it, but by a sheer miracle, I won this beautiful camera that was manufactured in West Germany between 1949 and 1950, according to the serial number.

When the camera arrived, a Zeiss Ikon Super Ikonta 531/2, it was in amazing condition. The 105mm f/3.5 Tessar lens was clean. The Compur-Rapid shutter operated smoothly and the times were perfect. And amazingly, the focusing lens travelled buttery smooth with the right amount of friction as to be just a tiny bit stiff. I have dreamt for years about having a Super Ikonta. Even though I prefer 6x6 or 6x4.5 frame sizes, I do like the 6x9 format, even though it does eat up a ton of film! One roll of 120 film in this camera will get you 8 shots! With today’s prices on film, that is not a lot. These cameras originally came with a 6x4.5cm mask. If any of you know where I can get one of these for a decent price, please let me know.

Due to this camera arriving so clean, I did some minimal cleaning and took it out for a test shoot. I took it out on the Peach Orchard Loop Trail that I’ve discussed before. It performed flawlessly. It was not the best time of day or season, but the detail captured in the large 6x9cm photograph blew my mind. I had a small issue with an old batch of 510Pyro during development, but the photographs still turned out well.

I look forward to using it again in the future. However, the use case for a wide format medium format camera is limited. I do landscapes, but as expensive as film is, I will have to be picky about when I use it. I still can’t believe I actually have one of these cameras. This model sells regularly on eBay for $249.

Below, you’ll discover photographs of the camera and the photographs it took. When I use it in the future, I will update this blog post.

NADD Copper Classic Dog Show

A dog and his best friend, the bone in mid air.

On Sunday, the 26th of January, 2025, we rode down to Surprise, AZ, a city to the northwest of Phoenix. Deana has a friend that shows Whippets, so we thought we’d go down and enjoy the show. It has been cold here for a while, thus it was a pleasure to go down to the valley where it was 66°F. In fact, the sun was beating down. The weather was, indeed, shorts and t-shirts weather.

We arrived a wee bit late. We were unable to see the entire show, but we still had a blast. I enjoyed photographing the AKC North American Diving Dogs. I took the Sony A7Cii, the LA EA5 adapter, Minolta Maxxum 70-210mm f/4, Minolta Maxxum 35-70mm f/4, and Viltrox 40mm f/2.5. The adapter and lenses worked great. There were a few instances when the lens focused out to infinity and back, causing me to miss the shot, but it did amazingly well for its age. I had character recognition turned on for animals, and it did not disappoint. It did not disappoint.

We hung out for a few hours and then headed home. After shooting over 400 photographs with the mechanical shutter and the adapter, it still had half a battery left. This camera has been a pleasure to use. Let me know what you think of the photographs. I’d appreciate your feedback. Thank you.

Minolta Maxxum 100-300mm lens w/ Sony LA EA5 Adapter

In this short review of the Minolta Maxxum APO 100-300mm f/4.5-5.6 lens, I discuss how well it works on newer mirrorless cameras with the LA EA5 adapter. I also provide sample photographs.

When I arrived home from work today, I grabbed the Sony A7Cii, the LA EA5 adapter that I discussed yesterday, and a Minolta Maxxum 100-300 f/4.5-5.6 lens. I headed down to the lakes at Green Valley Park in the hopes of photographing some wildlife. There were a lot of people out walking their dogs. The ducks were very photogenic. As I was walking around the lake in the hope of catching something somewhat wild, I discovered the same great blue heron that I had photographed on Wednesday.

The heron was standing regal, facing into the wind. He ignored me for the most part, perhaps because we had met before. He stood there for a bit, turning for me to get a good shot. The Sony A7cii has character recognition. It can detect animals and birds and their eyes. It is amazing how well it works. I took a $20 lens that you can purchase on ebay and got some amazing results. It does suffer from chromatic aberation, but most lenses from the 80’s do have this issue. In fact, some brand new lenses suffer from it.

You can spend $1500 and get sharper results, but why would you do that unless you’re shooting wildlife all the time and make money from it? It’s a logical question, right? I have all of these old AF Minolta A-mount lenses from the 80’s and 90’s. Why not make use of them. Some are better than others, of course, but they work surprisingly well with the new adapter. For any of you with a fairly new Sony mirrorless camera, get the adapter and a few A-mount lenses. You will not be disappointed. Below you’ll find a sample gallery from today’s shoot.

Sony LA EA5 Adapter

Last week, I ordered a LA EA4 adapter after doing a considerable amount of research about the five different E to A Mount adapters that Sony has offered over the years. These adapters are used to adapt older Sony and Minolta A-Mount lenses to modern Sony E mount mirrorless cameras. The first few iterations were clunky and the autofocus was slow. After doing a bit of research, I ordered the LA EA4 adapter. It arrived on Tuesday. When I got off of work, I peddled home in a hurry to discover to my horror that after waiting a week for the treasure, it turned out to not be supported for my camera, the Sony A7cii.

I put it on the camera, along with an A-mount lens that was supported by the adapter and nothing. I could adjust the aperture, but I could not get auto focus to work. I did more digging and discovered on Sony’s Japanese website that the LA EA4 is no longer supported and would not work on my camera. So, I disappointingly packed it back up and processed the return with Amazon. Once that was done, I ordered the LA EA5 adapter, which is cheaper and is supported on my camera and older ones.

It arrived yesterday, and to my incredible excitement, it actually worked like a charm! The great thing about the 5 over the 4 is that it doesn’t have a translucent mirror used for focusing, which means that all the beautiful light streaming through the lens hits the sensor directly without any interruption. I eagerly put a few of my favorite lenses on it, and to my delight, it worked seamlessly with each of them. Even better, the EXIF data transferred over perfectly as well, making the whole experience even more satisfying.

Early this morning, I headed down to Green Valley Park with the camera, the adapter, and a Minolta 35-70mm f/4 macro lens. The lens isn’t fast, but it is very versatile and a macro to boot. The lens is sharp and the autofocus, although not as fast as a native lens, is fast enough for what I do. I had a great time shooting with this lens and using autofocus. The subject recognition in the Sony A7cii does work through the older lenses. I had it on Animal/Bird, and it recognized a Great Blue Herons eyes and the subject. The autofocus is a little noisy compared to modern lenses, but for photography work, it is great. I will be taking the 70-200mm f/4 beer can lens out tomorrow to test it.

Thus far, I am incredibly happy with the performance of this adapter and the lenses used that I already have. This little adapter will save me thousands of dollars, and that, ladies and gentleman, is of the utmost importance. You can buy these old A mount lenses for pennies on the dollar compared to their native new counterparts. There are a few photographs below for your enjoyment. I could not get too close to the heron with a maximum range of 70mm. What are your thoughts on these adapters?

Favorite Medium Format Camera of 2024

A short review of the budget friendly medium format film camera with sample photographs.

In my previous post, I enthusiastically discussed my preferred 35mm film camera for 2024. However, I should have clarified that I was specifically referring to my favorite 35mm film camera of 2024. Today, I will shift gears and provide a detailed analysis of my favorite medium format film camera for 2024. What criteria led me to select this particular camera?

There are several important components to consider when picking out a favorite camera for an entire year of photography adventures. In my wee opinion, it absolutely has to be a camera that a person has put many rolls of film through over countless creative sessions. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, you need to truly enjoy using it. The camera must seamlessly become a part of you, almost like an extension of your own self, and you need to take the time to understand all of its wonderful quirks and genuinely appreciate them, as they often contribute to the magic of capturing unforgettable moments.

Every camera has quirks. This camera has a few, such as the slower top shutter speed, but the ease of use and versatility make up for it. I am referring to the Agfa Isolette I. This camera is an amazing medium format camera for the money. It is a standard 6x6 folding camera with an Agnar 85mm f/4.5. It modern times, that aperture seems slow and small, but it was great for its time. These can be purchased on eBay for around $20-$50 in decent condition. I’ve had three of these and never had a problem with the bellows or light leaks.

When shooting with these folders, I’m usually in bright sunlight and shooting at f/8, so the slow 1/200th of a second shutter speed isn’t that bad. It is fast enough. Below, I’ll have a few sample that I took with this camera. One thing to be careful of is double exposing (exposing the same frame of film twice). There is no safety, so you have to remember to wind to the next frame. My cheat for this is to go ahead and wind to the next frame as soon I take a shot. I still do it on occasion.

This camera purchase was pure luck, really. I decided to put in a bid of just $10, thinking it was a fun experiment, and a few days later, I was pleasantly surprised when I received the notification that I had won the auction. Not only did I win the camera, which turned out to be in fantastic condition, but I also scored a case and a little rangefinder tucked away in its own pouch! As I examined the photos of the ad, I noticed the rangefinder pouch attached to the case strap and immediately recognized exactly what it was. I took a chance and ultimately secured a wonderfully charming little camera and rangefinder duo. Together, they are an absolute joy to use, and I can’t imagine my photography adventures without them. Without a rangefinder, it would undoubtedly be a significant struggle to accurately guess the distance with my limited vision.

Keep all of this in mind when looking at these cameras. They do not have a rangefinder or a light meter built in, so you either have to have really good eyes to accurately estimate distance and a light meter or only use it at infinity. Agfa/Ansco are, for the most part, one and the same. The 50’s.and 60’s cameras were of great quality for the price. The Agfa/Ansco that survived into the 70’s was of lesser quality, in my wee opinion.

The main point of all of these posts is to encourage you, the reader, to get out there and shoot stunning photographs, whether it is with a classic 35mm camera, a versatile medium format, or a large format. Photography is an adventure waiting to be explored! If you have any questions, comments, or thoughts about any of these articles and reviews that I create, please feel free to reach out and use the contact page. I’d love to hear from you and help in any way I can!

Affordable Film Cameras

In my venture to find the ultimate deal on a film camera, I have come across numerous offers, some may have seemed too good to be true.

That’s like that old saying goes, if a deal seems too good to be true, it probably is. I am more than half a century old and have had to learn this the hard way, as my journey through photography has been filled with lessons learned from both successes and mistakes.

The Minolta srT line of cameras can be had with a lens for $30 plus shipping, making them an incredibly accessible option for beginners and enthusiasts alike. Different models offer various features, but they are all great cameras that have stood the test of time. The lenses that come with these cameras are known for their accuracy and sharpness, capturing images that are true to life, as they say. That being said, if you are looking for that ethereal feel in your photographs, you’ve got to try a Pentax as well, as they offer a unique quality that can elevate your work significantly.

The Pentax ME Super can be purchased on eBay for between $30-$50 with a lens, which is another steal in the world of film photography. They are equipped with full auto exposure control, yet also offer manual control with two convenient buttons on the top plate, allowing for flexibility in shooting conditions. The K1000 stands out, of course, because of its reputation and usability, but they are selling for upwards of $200 at present in December 2024—showing how highly regarded they are among film photographers. However, the ME Super presents a nice compromise and serves as a great camera for the price, combining quality and affordability seamlessly.

An older, but superior in my opinion, Spotmatic, can sometimes be acquired within the same price range and usually comes bundled with one of the amazing Takumar lenses. While these cameras may often show signs of age and require some TLC, they are well worth the time and effort you invest in them.

Another hidden gem from behind the iron curtain are the Praktica cameras. The MTL line of SLRs was amazing in its own right, blending functionality with reliability. We all take a chance when purchasing one of these cameras, but when they work, they perform exceptionally well; the lenses are absolutely stunning and sharp, producing images of remarkable quality. The Zenit cameras were good as well, though their lenses were generally regarded as superior to the camera bodies, which often seemed to present a problem.

Regardless of what you end up with, the essential point is to get out there and shoot some film. My entire goal is to inspire you, the reader, to rise up from your seat and start your photography journey. Whether you’re using a $5 point-and-shoot from a charity shop or a vintage SLR, the important thing is that you’re actively capturing moments; at least you’re doing more than the guy that talks about it all the time without ever picking up a camera. Get out there, embrace the adventure, and shoot!